About

The Meaning Behind Winter Solstice

Winter Solstice, known as Dongzhi (冬至) in Chinese, refers to the “peak of winter”. It’s the last Chinese festival of the year and because of its nature, nourishing food such as mutton is traditionally eaten together as a family. Thus the festival is often deemed as a time for family reunions! In Singapore, tangyuan is usually eaten to commemorate the festival. It’s also known as the Farmers’ Festival – with many giving thanks and celebrating on this day for the year’s bountiful harvest.

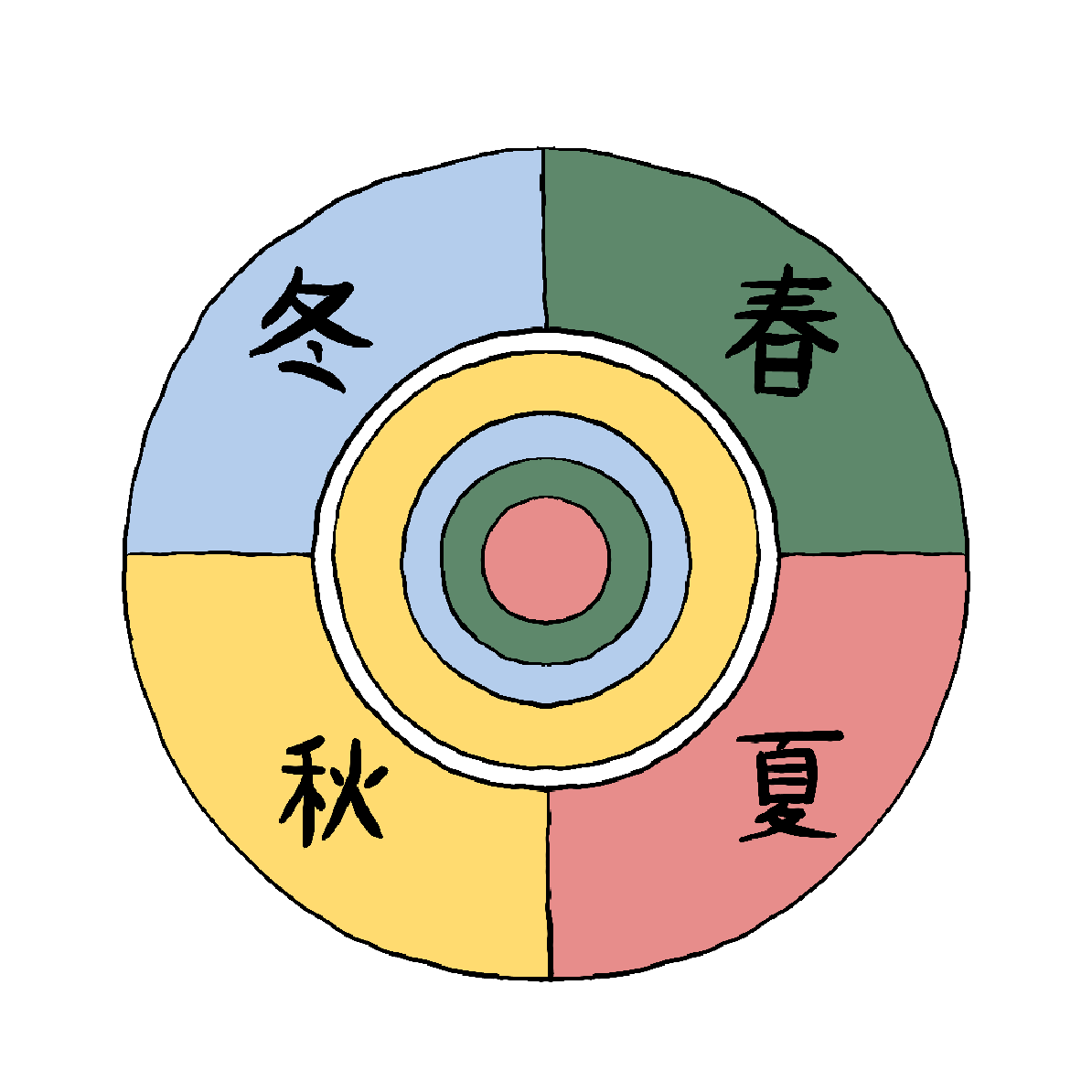

Winter Solstice is the 22nd of the 24 solar terms and usually falls on the mid-point of the 11th lunar month, around the end of December. On this day, the Northern Hemisphere tilts furthest away from the sun, making it the shortest day of the year.

The ancient Chinese believed that as days became longer after the Winter Solstice, positive energy, yang (阳), would return to Earth. This made Winter Solstice an auspicious day worth celebrating!

- Leon C. (2009), Through the Bamboo Window: Chinese Life & Culture in 1950s Singapore & Malaya, Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd and Singapore Heritage Society, p. 48

- Asiapac Books. (2012). Chinese Folk Customs. Singapore, p. 79

How was Winter Solstice celebrated in the past?

Did you know that in olden times, Winter Solstice was also known as the “Little New Year”? The eve of Winter Solstice was regarded as the last day of the year, so people would celebrate. But when the Emperor Wu of Han decided to fix the new year on the first day of the first lunar month, people no longer celebrated the “Little New Year”. Eventually, people celebrated Winter Solstice by exchanging greetings as if it were a New Year festival and those away from home would return to celebrate the festival with their families. Chinese opera performances were also held in the villages and offerings were made to the gods.

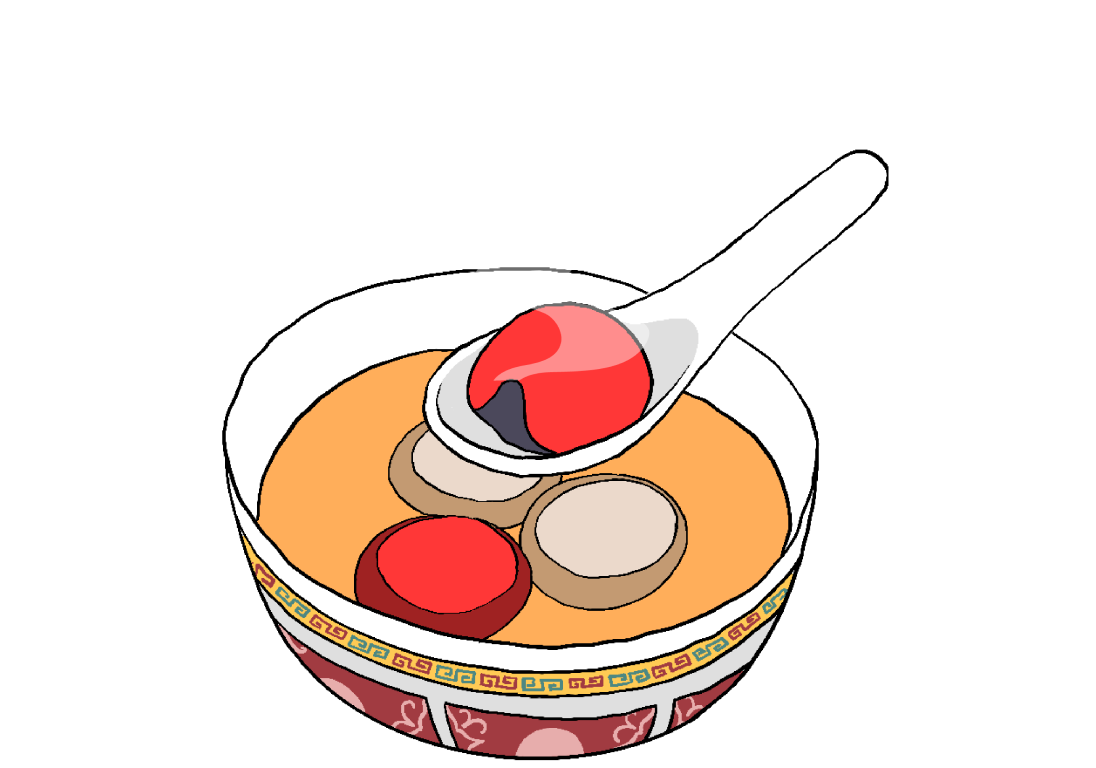

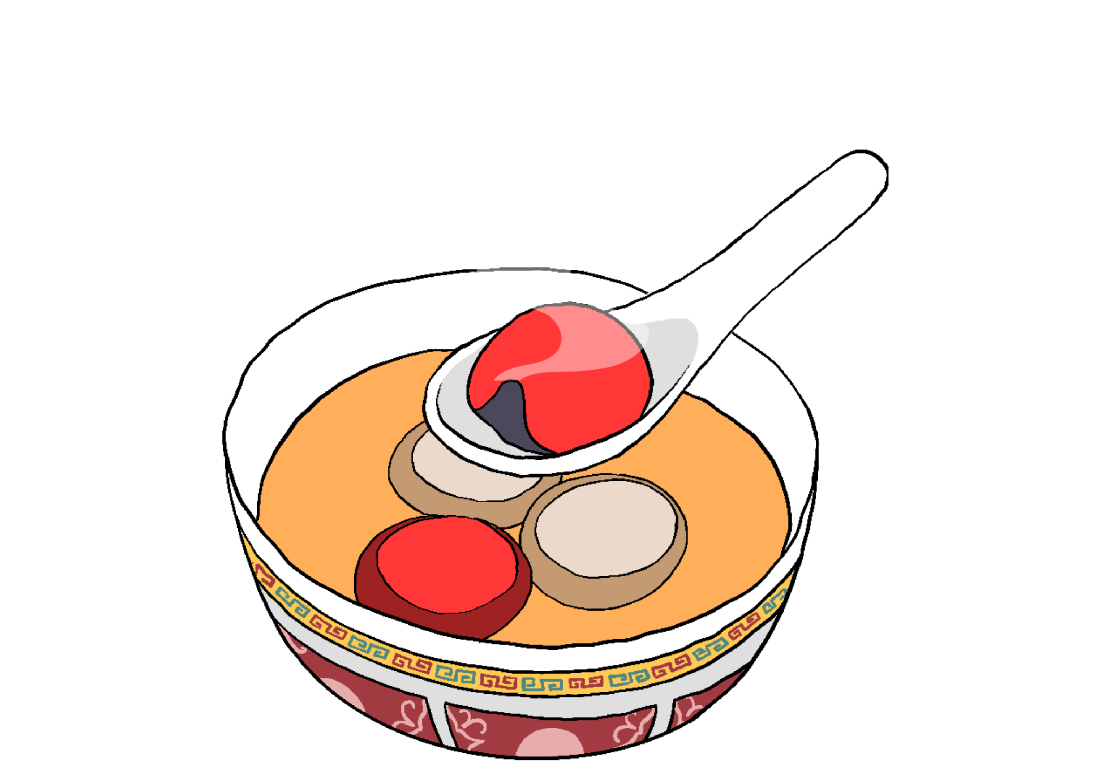

With all Chinese festival celebrations in Singapore, there’s bound to be an iconic delicacy and Winter Solstice’s is tangyuan (glutinous rice balls)! This sweet treat’s name, tangyuan, which sounds like tuanyuan (“reunion” in Chinese), symbolises family unity and harmony as well. A story goes that a pair of poor father and daughter arrived at a small town in Fujian. The daughter stayed on to work for a family. Before the father left, they each had half of the same tangyuan and promised to eat a full tangyuan when they reunited. On the next Winter Solstice, the daughter made two big tangyuan and pasted them on the main door, hoping that her father would come for her. Finally, the father showed up and they reunited.

In Singapore

These soft, gooey glutinous balls are usually filled with black sesame or peanut paste, and cooked and served in a sweet ginger or peanut soup.

Info source:

- Asiapac Books. (2012). Chinese Folk Customs. Singapore, p. 79

- Leon C. (2009), Through the Bamboo Window: Chinese Life & Culture in 1950s Singapore & Malaya. Singapore: Talisman Publishing Pte Ltd and Singapore Heritage Society, p. 48

- Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations. (1989). Chinese customs and festivals in Singapore. p. 81

How did the Winter Solstice Make Its Way to Singapore?

As our forefathers journeyed to Singapore in search of a better life, they brought along with them their diverse cultures and traditions in celebrating Winter Solstice. In Singapore, the Winter Solstice was also a time for reunion and for people to visit temples and pay respects to their ancestors. Steamed buns in different colours and shapes of animals like chicken, duck, dog, and cats, which symbolised a family’s thriving livestock, were also prepared for ancestor worship.

However, the Winter Solstice celebration has evolved over time in Singapore due to our diverse ethnic makeup.

Info source:

- NewspaperSG – Chinese Clansmen Remember Ancestors

- NewspaperSG – The Chinese Have Their Xmas Too

- NewspaperSG – It’s Their Christmas Day Too Today

- 新加坡福建会馆 (2009) 阮这世人- 新加坡福建人的习俗. 新加坡: 新加坡福建会馆, pp. 108-109

Image source: Big steamed buns for a prosperous New Year (1/6)